Ideomotor apraxia can be frustrating. This neurological condition occurs not because of muscle weakness but because of a disconnect between intention and movement.

When someone with ideomotor apraxia is asked to perform a familiar action (like waving goodbye or brushing their teeth) they may hesitate or perform the action incorrectly, even though they understand exactly what they’re being asked to do. It’s not a matter of “not trying hard enough.” The brain simply struggles to translate thought into action when prompted.

Whether ideomotor apraxia is the result of a stroke, brain injury, or neurodegenerative condition, there are ways to improve function and build confidence. In this article, we will take a look at what can help you or a loved one navigate daily life with more ease.

Let’s dive in!

What Is Ideomotor Apraxia?

Ideomotor apraxia is a neurological condition that affects the ability to carry out learned movements on command. The key here is that the person understands the request and often can perform the action automatically, however just not when they’re specifically asked to do it.

For example, if you ask someone to pretend to comb their hair, they might freeze or fumble. But if you hand them a real comb, they may start combing their hair naturally.

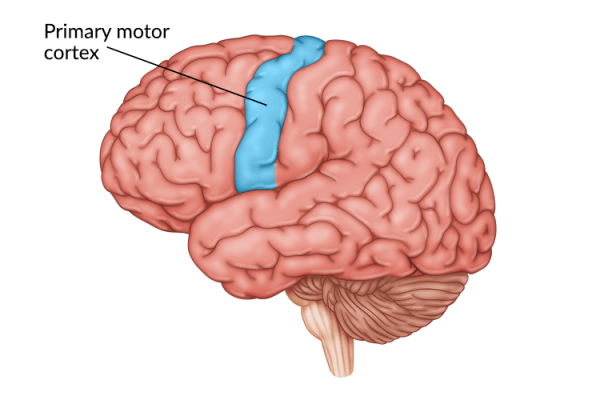

This difficulty is often linked to damage in the left parietal lobe or premotor cortex which are areas responsible for planning and coordinating voluntary movements.

Symptoms of Ideomotor Apraxia

Recognizing ideomotor apraxia can be tricky because the challenges often show up in everyday actions that most people take for granted. Rather than a lack of effort, these difficulties stem from the brain’s struggle to translate an idea into coordinated movement.

Common signs of ideomotor apraxia include:

- Difficulty miming tool use: For example, when asked to pretend to brush their teeth or hammer a nail, the movements may appear awkward or incomplete.

- Incorrect hand posture with objects: A person may hold a toothbrush or utensil in an unusual way, even if they know what it is for.

- Delayed or fragmented imitation: When asked to copy a gesture, such as waving, movements might be slow, broken into steps, or hard to coordinate smoothly.

- Better performance in spontaneous actions: Interestingly, many people move more naturally during unplanned tasks than when they are specifically asked to perform the same action.

These symptoms can be frustrating for both the individual and those around them. However, understanding that there is an underlying neurological cause helps shift the focus from “can’t” to “finding new ways to support everyday function”.

Ideational Apraxia vs Ideomotor Apraxia

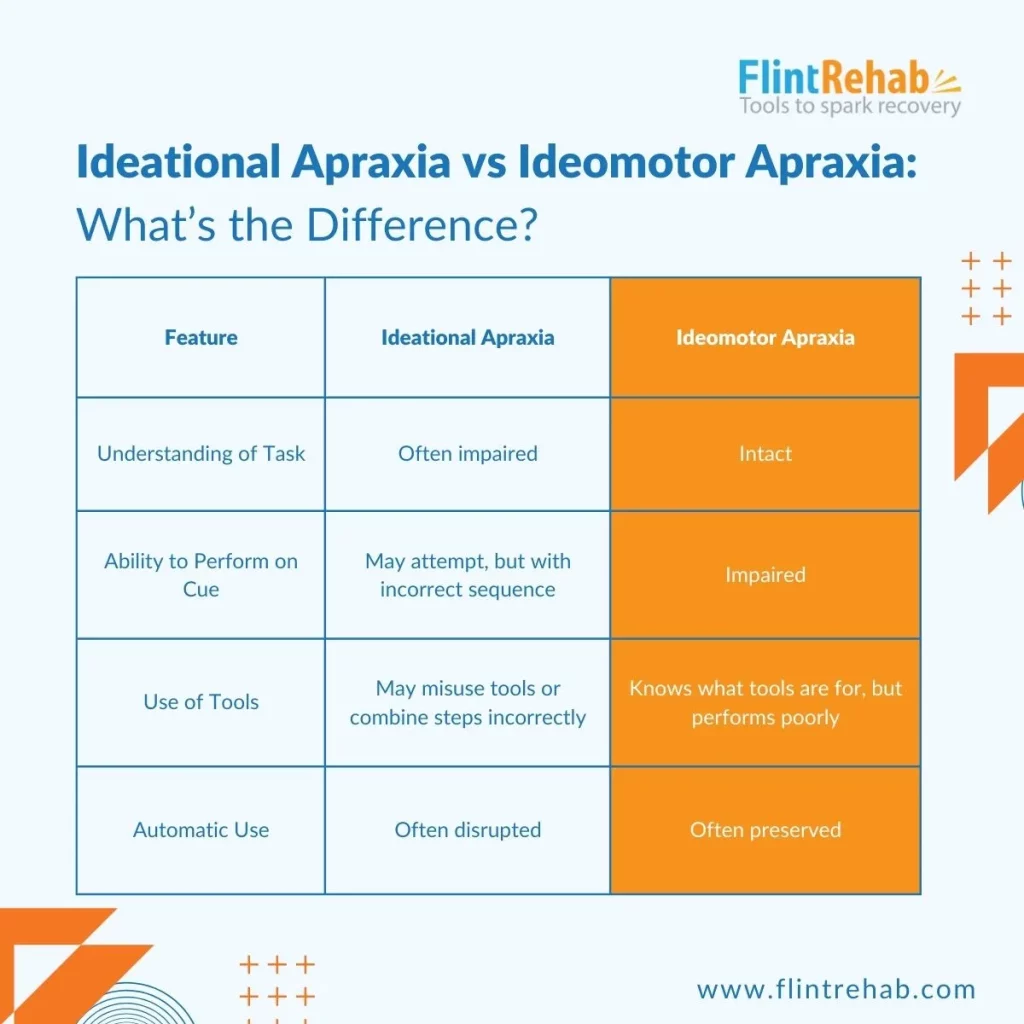

It’s easy to confuse ideomotor apraxia with another condition called ideational apraxia, but the two are actually quite different both in how they look from the outside and in how they’re managed.

Ideomotor apraxia affects how a person performs a single movement:

- They understand the action and what related tools (such as brushes, forks, cups, etc) are supposed to be used for

- They can often perform the desired action automatically

- When asked to perform or imitate an action on command, they struggle to initiate or complete it correctly

Ideational apraxia, on the other hand, affects what a person does. In other words, they have trouble with the overall sequence or idea behind using objects:

- They may try to write with a spoon or brush their teeth before putting toothpaste on

- They might skip steps or use items in the wrong order

- The concept behind the task seems disrupted

Here’s a simple comparison:

In addition, both types can co-occur, especially after brain injury or stroke. Recognizing the difference between each will help tailor treatment more effectively.

Now let’s take a look at several effective strategies that can help manage and improve ideomotor apraxia.

7 Tips to Manage Ideomotor Apraxia and Trouble With Learned Movement

Tip 1: Use Real Objects Whenever Possible

One of the clearest ways to support someone with ideomotor apraxia is to replace pretend actions with real objects.

Why it helps: The brain sometimes bypasses the faulty command-action pathway when a real object is present. Holding an actual toothbrush can trigger the motor memory of brushing teeth in a way that pantomiming cannot.

Try this:

- Instead of saying “pretend to brush your teeth,” provide a toothbrush and toothpaste.

- During therapy, incorporate tools like combs, cups, and pens.

- In daily life, keep commonly used objects accessible to encourage spontaneous use.

Over time, repeated exposure to real-world tools can help reinforce movement patterns and improve coordination.

Tip 2: Practice With Meaningful, Functional Tasks

Ideomotor apraxia affects intentional movement, but repetition of meaningful activities can help rewire brain connections. The key is to focus on tasks that matter to the individual.

That might include:

- Making a cup of tea

- Opening the mailbox

- Playing a familiar game

- Turning on the radio

These tasks are more likely to activate automatic motor routines than abstract movements or gestures.

Therapists often refer to this as task-specific training. Instead of working on general “arm movement,” the person practices real tasks like “picking up the phone.” This kind of repetition builds familiarity and confidence.

Keep in mind:

- It’s okay if progress feels slow.

- Focus on consistency and context.

- Encourage participation, not perfection.

Tip 3: Limit Verbal Commands When They’re Not Helpful

People with ideomotor apraxia often struggle more when they’re asked to perform an action verbally. Ironically, the more someone thinks about what they’re supposed to do, the harder it can become to do it.

In these cases, visual or physical cues may be more effective than spoken instructions.

Some ideas:

- Model the action yourself (e.g., wave goodbye instead of saying “wave goodbye”)

- Use picture cards to represent common actions like eating or getting dressed

- Gently guide the motion using hand-over-hand assistance

Of course, everyone is different. Some people benefit from verbal reminders. The key is to notice what helps reduce frustration and supports success and then lean into that.

Tip 4: Break Down Movements Into Smaller Steps

Complex movements can feel overwhelming to someone with apraxia. Even something as routine as brushing hair involves several steps: reaching, grasping, orienting the wrist, and moving in the right direction.

Try simplifying by breaking the task into one or two steps at a time:

- Focus on just reaching for the comb first

- Then shift to gripping it

- Only after that, guide the motion of brushing

This technique is sometimes referred to as chaining in occupational therapy. You teach one step at a time, then slowly link them together. This can be completed as:

- Forward chaining: work on completing small portions of the task in sequential order as described above, or

- Backward chaining: start by working on the end goal, in this case the motion of brushing. After this is mastered, add in gripping the brush before brushing, before finally working on completing the full process of reaching for the brush, gripping it, and combing the hair.

Both forward and backward chaining can be effective strategies – which one works best simply depends on the task and the specific individual.

Why it works:

- It reduces cognitive load

- It gives the brain a better chance to “find the path” for movement

- It supports confidence by building on small wins

When one step becomes automatic, add the next.

Tip 5: Establish a Routine With Visual Cues

Predictability can be comforting when movement feels unreliable. Establishing a consistent daily routine helps reduce the demand for spontaneous motor planning — something that’s particularly difficult for those with ideomotor apraxia.

One way to do this is by using visual schedules:

- Create a picture-based routine board (e.g., morning activities with images for brushing teeth, eating, getting dressed)

- Use sticky notes with short instructions near relevant areas (like “turn knob left” by the stove)

- Post photos of tasks in progress (e.g., a picture of someone zipping a jacket near the coat rack)

These cues don’t just remind someone what to do but rather they reinforce the idea that the action is achievable. This often helps reduce hesitation and increases follow-through.

Tip 6: Work With a Specialist (and Make It Collaborative)

Ideomotor apraxia can sometimes be mistaken for a lack of effort or understanding, especially if someone has intact strength and language skills. That’s why working with an occupational therapist, particularly one skilled in treating neurological conditions, is so important.

Therapists can:

- Assess which movements are most impacted

- Design customized activities

- Use evidence-based techniques like errorless learning, hand-over-hand guidance, and motor imitation

Caregivers can be active participants too. Sit in on sessions when possible and ask what strategies you can continue at home.

Questions to ask your therapist:

- “What movements does my loved one do better spontaneously?”

- “How can we practice outside of therapy?”

- “Are there specific objects or settings that help?”

Remember, the goal isn’t perfection. It’s about building independence, step by step.

Tip 7: Be Patient, Celebrate Small Wins, and Adjust Expectations

Progress with ideomotor apraxia rarely happens overnight. The brain is learning to navigate around damaged pathways and build new connections. This process called neuroplasticity takes time, repetition, and compassion.

Here’s what helps:

- Notice what’s going right, even if small: “You reached for your spoon without hesitating!”

- Let go of comparisons, especially to past ability or to others

- Adapt tasks instead of avoiding them: for example, using Velcro shoes instead of laces still promotes independence

Apraxia doesn’t mean someone is “not trying.” It means their brain needs different kinds of support to do what once felt automatic.

When caregivers and individuals approach challenges with curiosity instead of pressure, it makes the learning process much more productive.

Bonus Tip: What About Mirror Therapy or Video Modeling?

Some people benefit from seeing their own movement (or someone else’s) through a mirror or video.

These techniques may include:

- Mirror therapy: watching the unaffected limb (or the healthy limb of a caregiver or therapist) in a mirror to simulate movement in the affected side

- Video modeling: showing a video of a specific task being performed (ideally by the person themselves)

- Self-watching: practicing in front of a mirror to get visual feedback

- Virtual reality: completing a simulated task through immersive virtual reality with immediate visual feedback

While more research is still needed on how effective these approaches are for ideomotor apraxia specifically, they may support body awareness and coordination.

Talk with your therapist to see if these strategies are appropriate, and experiment to see what feels helpful.

Final Thoughts: Movement Is More Than Just Muscle

Ideomotor apraxia can challenge how we see movement. It’s not just a physical action but a coordinated process involving thought, intention, memory, and motor planning. And when that connection is disrupted, it can affect independence and confidence.

But progress is still possible. With consistent practice, creative strategies, and the support of caregivers or therapists, many people find new ways to reconnect thought and action. Recovery may not be quick, but each small step forward carries meaning which helps individuals regain not just function, but also a sense of control and hope.

We hope you enjoyed this article!