Imagine trying to read a sentence, but your eyes can’t move smoothly from one word to the next. Or you’re in a conversation, and instead of simply looking at the person speaking, your head turns sharply because your eyes can’t shift on their own. This is what life can feel like for someone with oculomotor apraxia, a condition where voluntary eye movements, especially quick gaze shifts, become unexpectedly difficult.

While the condition may sound rare or even minor at first, its impact on daily function can be significant. Whether it affects a child learning to read or an adult recovering from brain injury, oculomotor apraxia interferes with how people interact with the world visually.

In this article we’ll take a look at what causes this condition, how doctors diagnose it, and the different ways to manage it from treatment to simple strategies that make life more manageable.

Understanding Oculomotor Apraxia

Oculomotor apraxia, or OMA, is a neurological disorder where the brain struggles to initiate or coordinate voluntary eye movements, especially saccades. Saccades are those quick, darting movements our eyes make when scanning a room, reading a sentence, or following a conversation.

For someone with OMA, the brain’s message to “look left” or “look up” doesn’t trigger the expected eye movement. Instead, the eyes may hesitate, stall, or fail to move at all. Over time, many people develop adaptive behaviors, such as moving the entire head in the direction they want to look to make up for what the eyes won’t do on their own.

This condition doesn’t reflect laziness or inattention. It’s a genuine disruption in the brain’s ability to guide the eyes and it can be extremely frustrating, especially when others don’t understand what’s going on.

What Causes Oculomotor Apraxia and Makes the Eyes Stop Listening to the Brain?

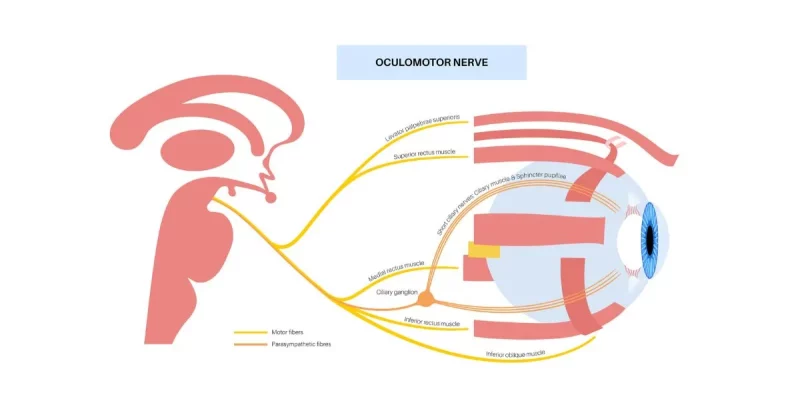

To move the eyes smoothly and purposefully, multiple parts of the brain must work together. It’s a delicate choreography that involves several areas of the brain, including the frontal eye fields of the prefrontal cortex, parietal lobes, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and deeper brainstem pathways.

When one or more of these regions are disrupted, whether due to developmental changes, injury, or disease, the result can be a breakdown in eye control. This is the root of oculomotor apraxia.

In some people, this dysfunction appears early in life. For others, it emerges after a neurological event. The cause can vary, but the common thread is a disconnect between visual intention and movement.

Let’s take a quick look at each.

Types of Oculomotor Apraxia

Not all cases of OMA are the same. In fact, how and when the condition appears can shape everything from symptoms to recovery.

Congenital Oculomotor Apraxia (COA): When It Starts at Birth

Congenital oculomotor apraxia is present from infancy. Parents may notice their child isn’t following objects with their eyes or is making exaggerated head movements instead. As the child grows, delays in visual tracking and coordination may become more apparent, especially in school settings.

COA is often tied to genetic or structural brain differences, such as Joubert syndrome or ataxia-telangiectasia. These conditions may affect more than just eye movement, including balance, muscle tone, and even language development.

But not every child with COA has additional challenges. Some grow into their own rhythm, developing compensations and learning strategies that help them thrive.

Acquired Oculomotor Apraxia: When It Happens Later in Life

Acquired oculomotor apraxia tends to have a more sudden onset. A stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, or degenerative condition can disrupt the networks that control eye movement. One day, a person might notice that reading has become unusually difficult or that they’re moving their head more often just to glance around a room.

This form of OMA often appears alongside other symptoms, like poor balance, cognitive changes, or slurred speech depending on which brain areas are involved. And unlike congenital cases, acquired OMA may be more frustrating because the person knows what “normal” once felt like.

Symptoms of Oculomotor Apraxia: Subtle at First, but Hard to Ignore

Oculomotor apraxia doesn’t always announce itself loudly. In fact, its early signs can be mistaken for poor attention, learning difficulties, or visual fatigue. But over time, certain patterns emerge.

People with OMA may:

- Struggle to shift their gaze from one side to another

- Blink repeatedly before moving their eyes

- Avoid reading or complain of visual discomfort

- Use exaggerated head movements instead of eye shifts

- Take longer to scan their surroundings or follow movement

In children, these signs might be chalked up to behavioral quirks. In adults, they might be brushed off as tiredness or aging. But when these issues persist, it’s important to look deeper.

Diagnosing Oculomotor Apraxia: What To Look For

Diagnosis of oculomotor apraxia begins with observation. This could be by a parent, teacher, eye doctor, or neurologist. The key question is whether the difficulty lies in the muscles of the eye or in the signals that guide those muscles.

Unlike eye conditions that involve muscle weakness (like strabismus or abducens nerve palsy), oculomotor apraxia involves normal eye strength but poor control. A simple analogy to remember for oculomotor apraxia is the hardware works but the software glitches.

A neurologist may run a series of eye movement tests, asking the person to look quickly between targets, follow a moving light, or respond to visual and auditory cues. In addition, neuroimaging (such as an MRI) may be recommended to look for structural changes, and in children, genetic testing may offer clues about underlying syndromes.

Oculomotor Apraxia Treatment:

There is no one-size-fits-all treatment for oculomotor apraxia.

Treatment depends on the cause, severity, and whether it’s congenital or acquired. While there’s no “cure,” many people can improve function and compensate with the right strategies.

Let’s take a look at a few potential treatment options:

1. Vision Therapy and Neuro-Optometric Rehabilitation

Specialized optometrists and vision therapists can guide individuals through structured exercises that train the eyes to initiate and complete saccades more effectively. These exercises often include:

- Target tracking games

- Flashlight or laser pointer exercises

- Eye movement drills with increasing complexity

While it takes patience, many children and adults see improvement in reading speed, visual coordination, and even social engagement.

2. Occupational Therapy

In cases of acquired OMA, occupational therapists play a key role in helping people adapt to new challenges. They focus on practical strategies for:

- Reading comprehension

- Navigating busy environments

- Coordinating vision with movement

- Using adaptive tools (such as magnifiers or e-readers)

These therapists often help individuals regain confidence in their ability to function independently, even when full recovery isn’t possible. While most occupational therapists have a baseline knowledge of vision treatment strategies, some specialize in vision therapy, making them especially valuable members of your team.

3. Assistive and Rehab Technology

Technology can be a lifeline. Many tools can help reduce the strain of daily tasks which in turn makes the day more manageable.

Some of these include:

- Text-to-speech readers for reading comprehension

- Magnifiers or e-readers with larger font and spacing

- Speech-generating devices for children with co-occurring communication challenges

In addition, apps and games designed for eye training can provide motivation and feedback, especially for younger users.

4. Environmental Modifications

At home or in school, small environmental changes can reduce strain and create a calmer space for someone with visual challenges. Instead of overwhelming the senses, these adjustments can make daily routines feel more manageable:

- Reduce clutter: Clear, organized spaces help the eyes focus on what matters without extra distractions.

- Use visual schedules: Consistent cues provide structure and reassurance, making it easier to anticipate what comes next.

- Limit rapid or shifting stimuli: Minimizing flashing lights, busy patterns, or sudden changes helps reduce visual overload.

- Provide extra time for transitions: Moving between tasks slowly allows the brain to process information without feeling rushed.

Together, these simple modifications create an environment that feels more supportive and less overwhelming, helping individuals focus on learning, healing, and daily activities with greater confidence.

Can oculomotor apraxia improve with age?

Yes, particularly in children. The brain continues to develop and form new connections through adolescence, and many children show significant improvement over time. With practice, the use of compensation techniques also becomes more natural, making eye control challenges less problematic.

Is it possible to drive with oculomotor apraxia?

That depends on the severity. Some adults with mild forms retain the ability to drive safely, especially with adaptive strategies. Others may require assessment and guidance from a driving rehabilitation specialist.

Final Thoughts

Oculomotor apraxia may be unfamiliar to most people, but for those living with it, its effects are personal and persistent. Whether you’re a parent noticing your child’s struggles, a stroke survivor adjusting to new challenges, or a teacher trying to support a student — understanding this condition is the first step toward meaningful help.

With therapy, technology, and a supportive environment, the path forward becomes clearer. And while the eyes may take longer to move, progress is still very much in sight.

Want to learn more about apraxia? Apraxia and Brain Damage