Learned nonuse after stroke is a complication that affects many survivors. This takes place when an individual ignores or avoids their affected limb, often after a stroke has impaired movement on that side. If learned nonuse persists, it can lead to muscle atrophy and the loss of motor and sensory function.

While learned nonuse can progressively worsen a survivor’s function, it is also avoidable in many cases. In this article, we will help you understand what this condition is and why it happens after stroke. Then, we will discuss different methods of prevention and treatment.

Jump to a section:

What Is Learned Nonuse After Stroke?

Preventing Learned Nonuse Through Neuroplasticity

Addressing Learned Nonuse After Stroke

Using Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy to Reverse Nonuse

Overcoming Learned Nonuse After Stroke

What Is Learned Nonuse After Stroke?

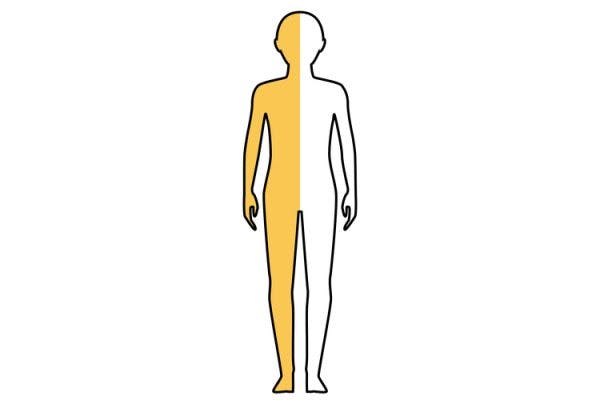

Learned nonuse after stroke typically occurs alongside hemiparesis, which describes weakness on one side of the body. To compensate for the weakness of their hemiparetic side, the stroke survivor will use their unaffected side for most activities. While this may be more efficient, not using the affected side will cause the survivor’s muscles to become progressively weaker.

With time, the survivor’s function on that neglected side will deteriorate until it is effectively nonexistent or completely suppressed. Therapists refer to this gradual reduction in function as learned nonuse. As you can imagine, this can have a major impact on a survivor’s function and independence.

If a stroke survivor’s non-dominant side is affected, learned nonuse can quickly follow. When a stroke weakens the non-dominant side of the body, it’s easy for survivors to subconsciously avoid using that side. Instead, they will often compensate with their dominant side for all activities since this feels more efficient. This is an example of how a survivor may slip into a pattern that promotes learned nonuse.

This can be even more prevalent when survivors experience unilateral neglect after stroke. This refers to a condition wherein a stroke survivor loses awareness of their affected side due to their specific type of stroke. Unilateral neglect can occur on the right or left, but left-side neglect is more common.

It is important to note that with left neglect, the person does not make a conscious decision to only use their right hand. Instead, they simply are not even aware that their left side exists. Whatever the cause of learned nonuse, the result is the same: decreased function.

Preventing Learned Nonuse Through Neuroplasticity

While learned nonuse is a serious concern, there are ways to avoid and rehabilitate this condition. The best treatment for learned nonuse is prevention. By working to increase your attention to your affected side and participating in rehab exercises, you can recover strength and awareness in your affected limbs after stroke.

Recovery of function can happen when you activate your brain’s neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize neural pathways in response to repetitive practice. This enables the brain to transfer functions previously controlled by damaged areas of the brain to other, healthy regions.

After a stroke, the neural connections between the brain and muscles can become weakened or interrupted completely. This explains why a survivor may experience hemiplegia or hemiparesis, referring to paralysis or weakness of one side of the body. In other cases, a survivor might lose strength in their hand following their stroke.

Whatever a survivor’s secondary effects, engaging the brain’s neuroplasticity allows them to rebuild those neural connections. With time, survivors can increase awareness of their affected side and regain control of their muscles.

Addressing Learned Nonuse After Stroke

In the previous section, we discussed how repetitive exercise can be used to activate neuroplasticity and recover function. In turn, this can help survivors avoid or reverse learned nonuse. However, some stroke survivors can face a dilemma here. How do you exercise your arm if it is affected by paralysis or learned nonuse?

The answer to this question lies in an intentional rehabilitation program. This is why working closely with your team of therapists is so important after stroke. Your therapy team will help you create meaningful goals after stroke and then customize your rehab program to allow you to meet those goals. Let’s review the different treatment methods you may utilize to avoid or reverse learned nonuse after stroke:

Rehabilitation Methods

- Physical therapy: Your physical therapist can help you address motor and sensory secondary effects including muscle weakness, decreased balance, reduced core strength, and gait (walking) impairments. In addition, they can help you overcome learned nonuse by drawing attention to your affected side and working to increase your muscle function.

- Occupational therapy: Occupational therapists can help you incorporate your affected side into activities of daily living such as bathing, dressing, cooking, and eating. Furthermore, they can help you increase your awareness of your affected side through sensory reeducation exercises.

- Passive range of motion: If you are affected by weakness or paralysis, passive range of motion exercises are a great place to start. This involves using your unaffected limbs or another person to help move your affected limbs through their range of motion. This engages neuroplasticity and can also help prevent contractures after stroke.

- Active exercises: Once you notice muscle activation in your affected limbs, you can progress to active exercises. These use your own muscle contraction to move your limb through the exercises, although you can use your other limbs to help. Your physical and occupational therapists can help you get started!

- Mirror therapy: Mirror therapy is an amazing tool that can be used by survivors with paralysis. This involves covering your affected limb with a mirror and performing exercises with your unaffected limb while watching the mirror. This can help draw awareness to your affected side and “trick” your brain into thinking your affected side is moving, engaging neuroplasticity.

- Constraint-induced movement therapy: This is a research-supported technique to help survivors overcome learned nonuse after stroke. It is one of the most effective ways to address this condition and may be suggested by your therapy team. Let’s explore this technique more in-depth in the next section.

Using Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy to Reverse Nonuse

Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is an intervention designed to prevent and treat learned nonuse after stroke. It involves the application of behavioral-analytic techniques to reverse motor deficits. Specifically, CIMT works by forcing the stroke survivor to use their neglected arm by constraining their unaffected arm.

The hope is that by exercising the affected arm, neuroplasticity will kick in and the survivor will regain the function of the limb. To constrain the unaffected arm, a therapist might have you wear a mitt to prevent you from using your hand. This forces you to use your weaker hand instead of compensating with your dominant or stronger side.

For CIMT to have its intended effect, survivors must practice it more than once or twice a week. Since the goal is to activate neuroplasticity, you will need to use your affected arm as often as possible. That’s why many therapists instruct their patients to continue wearing a mitt on their strong arm for up to 90% of their waking hours, including at home.

However, wearing a restraint alone for an extended period does not enhance the treatment results, according to one pilot study. Rather, survivors must engage in functional, intensive exercise as well. As you can imagine, CIMT can feel intense, and it can be difficult for survivors to stay consistent with this type of therapy.

This is where home exercise programs like Flint Rehab’s FitMi shine. This encourages patients to exercise regularly and to perform the massed practice necessary to maximize neuroplasticity. Through functional, intensive exercise, patients with hemiplegia or hemiparesis are often able to regain mobility and strength. When you use your affected side, the brain will respond and improve your awareness and function in those muscles. As the therapy saying goes, “Use it to improve it!”

Overcoming Learned Nonuse After Stroke

Learned nonuse is a serious but common secondary effect of stroke. This condition is acquired when survivors neglect their affected side and use only their unaffected limbs. With time and this nonuse, the muscles become weaker and function can be lost completely. This is even more prevalent when survivors are affected by unilateral neglect.

Fortunately, learned nonuse after stroke is treatable. The key to addressing learned nonuse is to engage with your affected side every day, incorporating it into as many functional activities as possible. This will activate neuroplasticity and help rebuild the neural connections to your muscles. Additionally, therapies like constraint-induced movement therapy can be incredibly beneficial.

Talk to your physical or occupational therapist for more information on CIMT and specific exercises you can try at home. Then, stay consistent with your rehabilitation program and continue to use your affected limbs as much as possible. With time and dedication, you can reverse learned nonuse after stroke.